A minor Twitter storm broke out a few weeks ago, as music fans reacted with incandescent rage to a piece of criticism from The Times’ poetry critic passing judgement on immortal lyrics penned by several of the most famous songwriters in Western music history.

Full disclosure, I thought it was a wildly misjudged article. But just as alarming was the accusatory manner in which several of the social media grumblers drew attention to the critic’s age. The insinuation was that a writer in their 20s couldn’t be expected to ‘get’ the lyrical references offered up by the likes of Bush, Bowie, Dylan et al, or the context in which they were written.

This poses an interesting conundrum: can a person who is distanced in time and culture from a musical ‘event’ still offer up a valid criticism of it?

There are no 300-year-old critics

As I scrolled through the Twitter storm, I wondered whether disgruntled middle-aged opera fans in early 19th Century Austria spent their time similarly engaged, spouting off over a Viennese coffee about how the kids at the opera house couldn’t possibly appreciate Mozart because they weren’t around during the classical hitmaker’s lifetime.

All of these people are now long dead. Yet, we’re still able to write about Mozart, to appreciate him, to criticise him, even to fictionalise his life and, in doing so, wilfully destroy the reputation of one of his contemporary composers.

Working to this logic, ‘being there’ is clearly not a prerequisite of legitimate criticism. Sure, it’s great to hear from the people who lived and breathed the scenes of music eras past, who remember what it was like hearing Johnny B Goode on the radio for the first time, who can articulate the cultural impact of the Beatles and the Stones with clarity and distinction because they were there when it happened. But their perspective cannot be the only game in town.

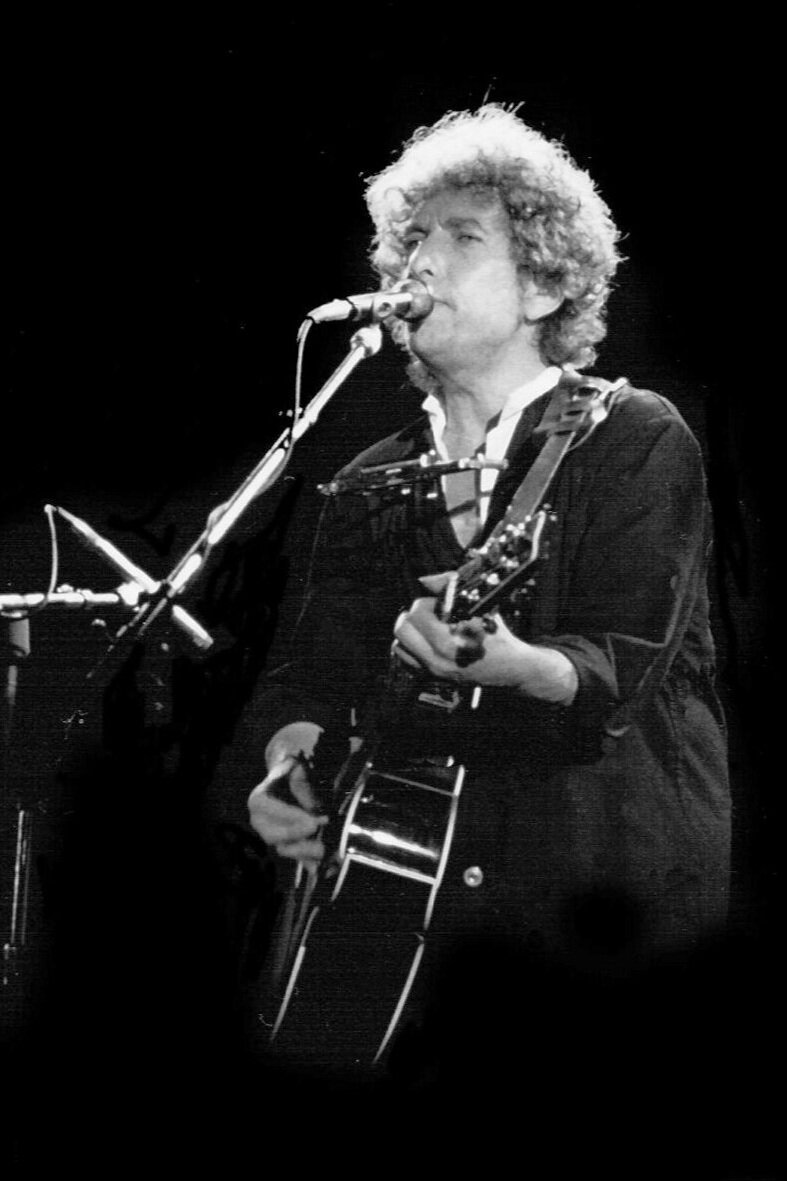

Take writer Clinton Heylin, for example. Heylin appears to believe he’s the only person qualified to write about Bob Dylan. He is on record dismissing the work of his Dylanology peers (including Dylan himself). And yet, he was born in 1960 and can have no meaningful lived experience of Dylan’s 60s heyday. By the time he reached adulthood, Dylan had already completed his comeback and was entering his religious period!

Now people may consider Heylin to be something of a pompous ass, but they don’t criticise him for failing to be 10-15 years older. Surely criticism ought to be considered on its own merits, irrespective of how old the critic is or whether they were part of the relevant music scene at the time?

All things must pass

Much has been made of the idea that 2016 was an annus horribilis for the music world, featuring a procession of legendary artist deaths including David Bowie, Prince, Leonard Cohen, Glenn Frey, Merle Haggard, both Emerson AND Lake, amongst others.

But our collective fixation on 2016 diverts attention from the fact that the following year saw the deaths of Chuck Berry, Gregg Allman, Chris Cornell, Glen Campbell, Walter Becker, Malcolm Young, David Cassidy, Tom Petty and Fats Domino, while in 2018, we lost Aretha Franklin… I’ll leave it at that; otherwise this is going to get far too depressing.

Scores of legendary artists have died in the past few years. A lot of them were very old. Doubtless, the majority did not live particularly healthy lives. As Ian Dury once sang, “Sex and drugs and rock and roll is all my brain and body need.” This philosophy of living, while admirable, is not especially well-aligned with the pursuit of longevity. Once you add booze to the list, you have the history of modern music in a nutshell.

It’s morose to speculate how long it will be before we lose all living links to our musical past. But this is how time and history work. Inevitably, as the years pass, we’ll become more and more distanced from these musical legends and the culture in which they existed.

Old tunes, new audiences

I’d argue that it’s in every fan’s interests to ensure the best creative work lives on in contemporary culture, and this means enabling and encouraging criticism. Music criticism plays a vital role in keeping artists’ legacies alive, renewing and reviving their work for subsequent generations rather than reducing it to a matter of historical record. As so many musical superstars shuffle off this mortal coil, it’s never been more important that this baton gets passed to the younger generation.

If people grow up believing that certain artists are beyond reproach, or they get shot down every time they attempt to volunteer their perspective, the most likely outcome is that a sizeable proportion of the old-school artists venerated by ageing music fans today will simply be ignored by the music fans of tomorrow.

This is not to say that criticism should go unchallenged. Quite the opposite. Whether a critic is aged 25 or 75, the person who does their homework, work through their arguments and acknowledge any limitations in their perspective (i.e. the fact they weren’t around at the time) will be far better placed to win a debate than the person who peddles a slapdash response.

But we should also acknowledge that music is subjective. If, as a species, we have yet to determine conclusively why homo sapiens find it necessary to produce music in the first place, shouldn’t we allow the young rapscallion at The Times his right to claim that the lyrics to ‘Running Up That Hill’ aren’t truly poetic? Even if he’s clearly wrong.