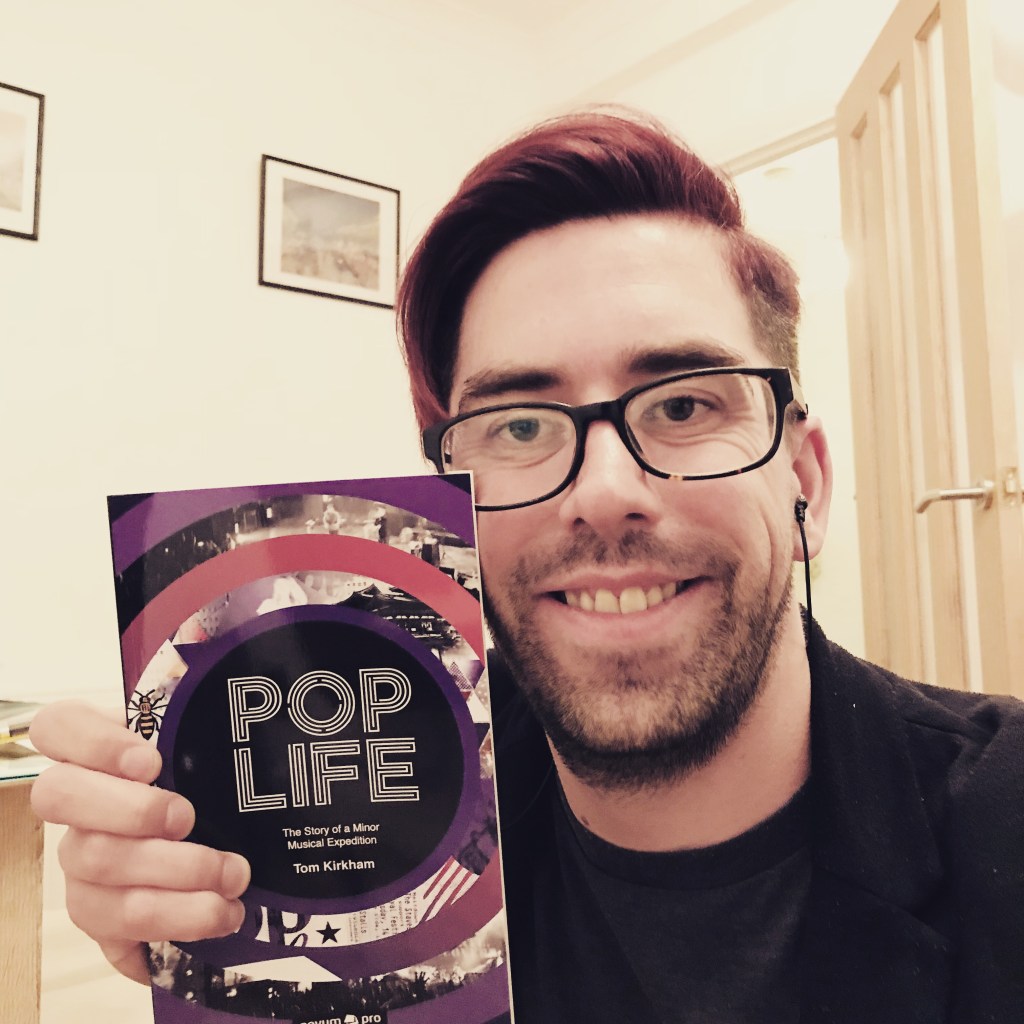

Almost a decade ago, I wrote a book called Pop Life, charting my circumnavigation of the London music scene over 12 months as I attempted to rebuild my battered mental health.

By the time it was published, I was well underway with the follow-up. It was an altogether more ambitious undertaking in which I fictionalised myself as a struggling author trying – and failing – to write a genre-defining work of travel literature, then added a second, wholly fictional protagonist with an interwoven narrative.

After two and a half years of endless writing and rewriting, I finally finished my manuscript, secured a contract with a small independent publisher, and began to contemplate editing, cover art, and PR support. It was now or never; to be seen as a legitimate author, I needed it to succeed.

Then came the pandemic – not good news for publishing, or indeed, the rest of us.

The book was not published, and after a prolonged period of false dawns and waning enthusiasm, I gave up all hope that it would see the light of day. What’s more, since I finished the manuscript, my life has changed beyond recognition, and I no longer resemble my semi-fictional self. I now have a child. I no longer live in London. I’ve become a homeowner. I have learned to drive. My cat is dead.

And so, when my publisher got back in touch to share a proposed front cover, followed soon after by the long-awaited edit of my manuscript, I was more than a little taken aback.

Since then, I’ve spent two months trying to reinsert my head into my old life – and a partially fictionalised life at that. It’s been a terrible experience. I barely recognise the Tom I put down on paper seven years ago. He’s in a state of permanent frustration – weighed down by his depression and convinced that the only answer is to get away from everyone and everything. He has gone off the rails and is not himself.

I’m referring to myself in the second person to emphasise the extent to which time, circumstance and experience can change people, and to suggest that perhaps our society ought to be more forgiving of past errors and (mis)behaviours. The phrase “I wasn’t myself” has become cultural shorthand for moral evasion, but in my case, I’m really not trying to evade anything. I’ve been trying to publish this expose of my personal shortcomings for years!

I’m certainly not alone in wishing to distance my current self from my former. We’ve all done things we regret – the unappreciated pass at a colleague, the misjudged fancy dress costume, the moral lapse that led to the bigamy incident.

Not everything in this life can be readily forgiven: case in point, Prince Andrew. But it strikes me that we are living in a particularly unforgiving age, where even the most heartfelt and sincere apologies frequently fall on deaf ears.

A colleague recently told me that their former boss had a professional mantra of “never apologise” and instructed her entire team to behave the same way. Many popular politicians of our time appear to have taken note.

While I cannot advocate for such a position, I can see why, if large swathes of our society are unwilling to accept any form of apology, others might stop offering them in the first place.

The demise of the apology is a worrying prospect. We have names for societies where those in power act with reckless abandon and disregard for consequence, as well as for those in which no one is allowed to do anything wrong, ever.

So there we have it – the collapse of human civilisation is imminent. And while we await this self-inflicted apocalypse, I have but one ask of you, dear reader: buy my book.

Leave a comment